When Coronavirus spread out of Wuhan to the world, both Fatima (36 years) in Rokban refugees’ camp in the Syrian desert, and Ro’aa in Idlib’s countryside, were halfway through their pregnancy.

The two Syrian women did not know that the virus will expose them and their unborn babies to new dangers.

Fatima lives with her family in Rokban Syrian refugees’ camp, in the south east of Syria, an area that was secluded from the world when the camp was established six years ago, locked up between the Jordanian borders, an American military base, and Russian “humanitarian” crossings.

Fatima had no idea where she could give birth to her baby, after the Jordanian authorities closed the sole medical facility inside Jordan’s borders, as one of the measures for fighting Coronavirus.

Simultaneously, Ro’aa was afraid that her baby might need a ventilator, not available in Idlib, while the Turkish authorities have suspended receiving “medical emergency cases” from Syria, also in context of Coronavirus preventive measures.

This happens while the lockdown measures have exacerbated the already tragic situation of Syrian pregnant women in camps, with insufficient basic healthcare.

Coronavirus has weighed heavily on pregnant women throughout Syrian areas, especially the most fragile in terms of healthcare and food availability, in refugees’ camps inside Syria. Hence the idea to investigate and shed light on this situation.

According to a physician in the city of Hassaka, the most dangerous impact of the virus in the case of a pregnant woman is due to that she already suffers shortness of breath, during pregnancy, thus being infected with the virus endangers her body further, causing her to have less immunity compared to non-pregnant women. This problem is exacerbated by the difficult access to hospitals.

Throughout the recent years, the role of the medical facility on Jordan’s borders was to transfer critical cases from Rokban camp, including pregnant women who need c-section operations or healthcare, to the hospitals in Jordan. This was also the case with newborns in need of NICUs, phototherapy for jaundice or ventilators.

On the other side of the country, pregnant women in northern Syria continue to fear for their newborns’ lives in case they needed medical care, while it is difficult to transfer such cases to Turkey in the time of the virus.

"Where will I give birth?"

“Where will I give birth?” Fatima, pregnant in her seventh month, and living in Rokban camp, keeps asking. “Following the suffering of women during delivery is harder than experiencing the danger itself. I see my destiny in these women who need c-sections and have nowhere to give birth.”

“I fear any scenario in which I need a c-section or my newborn needs healthcare, or an NICU,” she adds, “In such cases either me or my newborn will die.”

Fatima, who hails from Homs province, suffers from lack of basic food. She does not eat fruit, and she gets no medicine, vitamins, or food supplements, while the follow-up of her pregnancy is provided in the “Tadmor medical post” inside the camp, which lacks the requirements of basic medical care.

During her last doctor’s visit, before Coronavirus lockdown was imposed, Narmeen was told she has anemia, and her baby suffered from malnutrition. He prescribed some medicine for her, but she could not afford to buy them

We obtained photos of Tadmor medical post, which is built of mud with few rooms, containing worn out furniture thrown on the floor, besides some first aid kits. It is obvious that the post is not fit for any medical procedures. Medicine is scarce and delivered through smuggling while not enough for pregnant women needs.

On April 11th, the “Public and Political Relations Authority in the Syrian Desert,” made a call for help to the government of the United States of America via the military base in Tanaf, after the siege of the camp was tightened.

The authority spoke, in a statement, of the food and health crises due to the UNICEF post having been shut down, and the Syrian regime siege of the camp. “The people of the camp face a health crisis, as several pregnant women need c-sections, with no means to provide any, because of closing the camps, and the inability of pregnant women to go to the territory of regime forces, for security reasons, fearing detention” said the authority concerning the pregnant women.

The authority requested from the US immediate aid through the Global Coalition forces in area 55, and to save the lives of mothers and their children.

Giving birth in the military base

Last April, two Syrian women had to go to the American military base in Tanaf to have c-sections, it was the only option they had.

According to what the British newspaper The Times, the officer physician in charge in the base was not specialized in delivery, and knew little about it, but he carried out the c-sections. He was helped by a colleague monitoring the operation throw video conference from the US.

On his side, Shokri Shehab, the manager of Tadmor medical post, which is under the authority of the Council of Tadmor and Syrian Desert Clans, has pointed out that two experienced midwives from the camp accompanied the two women in the military base during the c-sections.

“There are 30 to 40 deliveries in the camp monthly,” Shehab says, “we used to refer them to the UNICEF post, which in turn transferred the women to Jordan’s hospitals.”

The UNICEF post used to follow-up pregnancies, and provide pregnant women with medicine and food supplements, in addition to transferring newborns in need of NICUs and phototherapy to hospitals in Jordan, while natural deliveries and caring for pregnant women were carried out in Tadmor medical post inside the camp and under the supervision of the only two midwives there.

In his turn, Shehab emphasizes that Tadmor post is not ideal, but it is the only one available under the current conditions, pointing out the damage inflicted on pregnant women after the closure of the UNICEF post, especially that there is not a single physician in the camp housing 11,000 civilians.

“Even if the UNICEF post is reopened,” he continues “its working hours used to be from 9:00 AM till 3:00 PM, and no emergency cases were admitted out of these hours.”

Concerning the camp’s needs when it comes to pregnant women and newborns, Shehab explains that there is an urgent need for oxygen devices in the least, for reviving newborns who are short breathed, so as not to consider their death inevitable.

Like the medical siege the camp faces a total siege as entry of relief aids is totally forbidden, thus depriving civilians in the camp from vegetables, fruits, and basic foods besides wheat and flour, which are smuggled into the camp. Accordingly, pregnant women do not have enough nourishment, which increases the probability of their newborns needing NICUS.

Jordan’s response was quite clear concerning the reopening of the border’s UNICEF post. As per Ayman Al- Safadi, the Jordanian minster of foreign affairs, his country will not allow any relief aid into the camp through its territories, nor will it allow the entry of any person form the camp to Jordan’s territory.

“Protecting citizens from the Coronavirus pandemic is an extreme priority for Jordan.” Said Al-Safadi in a phone call with the UN special envoy to Syria, emphasizing that the responsibility of Rokban’s camp is both Syrian and international, as it houses Syrian citizens on Syrian lands.

He also explained that any humanitarian or medical aids needed by the camp can enter through Syrian inlands, emphasizing the necessity of international cooperation for obtaining a political resolution in Syria.

Newborns in danger

In Northern Syria, under opposition control, there are other kinds of fears. It is true that the hospitals and doctors there are capable of carrying out c-sections and natural deliveries, but in case of any health emergency for the mother or the baby, or the last being in need for NICU, everybody becomes helpless in face of the inevitable end.

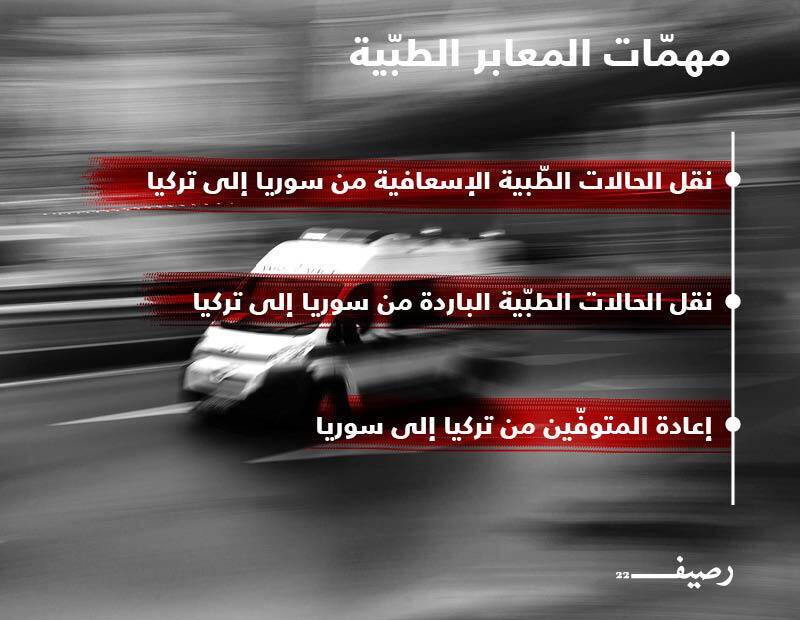

Previously, newborns in need of NICUs, phototherapy or any other healthcare measures unavailable in northern Syria, used to be transferred to Turkey through land border crossings which are Grables, Bab Alhawa, and Bab Assalama.

As Jordan and Turkey close their borders to all travel, pregnant Syrian women needing C-Sections find themselves helpless and at risk. Documenting stories from pregnant Syrian women besieged by Coronavirus

Turkish authorities have recorded the first Coronavirus case last March 11th. After two days only, the Turkish authorities closed Bab Alhawa crossing in the face of civilians, while admitting only commercial and aid trucks, in addition to first aid emergency cases, as per a statement by the crossing officials.

After six days, the Turkish authorities closed both Bab Assalama and Alraie crossings, completely, while allowing the entry of medical emergency cases.

This however did not last, on March 26th, Turkey stopped the entry of medical cases as well, including the newborns who need NICUs or ventilators.

“The Turkish side stopped receiving medical first aid cases,” said PR official in Bab Alhawa crossing, Mazen Allosh, “causing a health care crisis in northern Syria.”

According to data on Bab Alhawa crossing’s website, more than 10,000 patients have entered Turkey through this crossing alone in 2019, coming from the Syrian north, and including 3942 first aid cases, with newborns and mothers among them.

In the first three months of the year, about 900 first aid cases have entered Turkey through the same crossing, aside from other crossings that admitted patients.

Vulnerability of medical infrastructure

Doctor Nazieh Alghawi points out the absence of statistics of the number of NICUs or ventilators inside Syria, explaining that there is “extreme and dire shortage” of these devices, according to his own follow-up of NICUs issue through “coordination rooms of the Syrian north doctors,” while the demand for these devices escalates due to the increasing number of newborns needing them.

Alghawi adds that babies born after 28 weeks of pregnancy are considered premature, such babies need NICUs to keep them worm and pulse and oxidation monitoring devices, besides ventilators and in sleep short breath monitoring.

He adds that newborns in need of NICUs are those whose medical conditions are not good due to having blue skin color, premature moaning, difficulties of breathing, rib suctions, or incomplete growth inside the womb.

Phototherapy, is needed if the newborn has an extreme case of jaundice, as failing to treat such newborn might lead to brain paralysis or atrophy.

The same doctor has emphasized the crossing closure “catastrophic impact” on pregnant women and newborns in northern Syria, pointing out that the closure was comprehensive leaving no exceptions even for medical aid cases, in time when the number of newborns who need to be immediately transferred to Turkey is increasing.

The doctor has also explained the medical conditions of newborns in northern Syria in time of Coronavirus, “the region began to be short on medicines, depriving patient from obtaining them for free. We also need beds, operation rooms, and intensive care units, both for newborns and adults.” He said.

One of the problems caused by the Coronavirus crisis, is malnutrition of pregnant women and newborns, and lack of food supplements which impact newborns’ health.

On her side, doctor Nagwan, head of pediatric division in motherhood hospital, warned that “continuing closure of the crossings will increase mortality rates of those who could have been saved in Turkey. It will also exacerbate the shortage of supplies in Syrian hospitals.”

Pregnant women in camps: Coronavirus exacerbated our tragedy!

Roba Al’ali, a Syrian woman living in Tell Al’aawar for refugees in Idlib countryside, spoke of her suffering as a pregnant woman inside the camp in the time of the Coronavirus.

“I have so many fears,” she says, “there are no places to sit or sleep comfortably inside the tent. I cannot get physical comfort during pregnancy. I also have no private space or clean and safe WCs.” Explaining that it would be catastrophic in case of the virus spread to the area.

Roba has also spoke of the absence of hospitals, thus most cases must be transferred outside the camp. She complained that while the pregnant woman and her newborn have vulnerable immunity, those in camps have even more vulnerable immunity due to lack of suitable food and the weak disease preventive measures.

On the other side, Sarah Ahmed, who lives in Frekeh camp in Idlib says: “we live under hard conditions in the camp. During my pregnancy, I have not had suitable food that pregnant women usually have, due to my husband being out of work and having no income, after the spread of Coronavirus.”

Sarah speaks of being afraid of the virus every time she has high temperature or short breath. She fears that her baby might catch the virus. Such fears affect the pregnant woman as well as her baby’s health, as the specialist doctor, Ro’aa Abbas points out.

Because of her husband being out of work, Sarah will not be able to give birth in a hospital that provides suitable services. She will give birth in one of the public hospitals, as she mentions. Such hospitals are far from the camp, which puts her in great physical dangers during moving in and out of the camp.

“I have not given birth yet,” she adds “but I have watched women giving birth inside the camp, and their suffering of diseases due to the living conditions unsuitable for a mother and her newborn.”

About Coronavirus and her pregnancy, Sarah says: “The hardest thing is the absence of isolations centers or a quarantine inside the camp. The population is large, making the tent unsafe during the pandemic time, which causes me to be worried all the time.”

On her side, Shaza Almostafa, a licensed midwife, says: “since the fears of the Coronavirus spread has started, many healthcare centers were closed, which negatively impacted the pregnant women. Two weeks ago, however, and till now, some centers reopened their doors, and pregnant women are coming back to them for healthcare.” She explains that she does not know the reason behind civilians losing their fears, though the danger of the virus still exists.

Almostafa points out that a newborn, also needs vaccines, but these were not available since the beginning of the Coronavirus time in northern Syria. They are gradually becoming available, now. Almostafa explains that in the fears period climax, pregnant women were not able to enter hospitals and medical centers except for extreme emergencies and under sterilization measures. Many pregnant and lactating women, going to hospital periodically for healthcare and free medicines, were deprived of this due to the closure of most centers.

Fear, then fear

In northeast Syria, under “self-administration,” there has been no siege by any party, but this did not reflect positively on pregnant women.

On March 23rd, the administration enforced a curfew throughout its territories, to prevent the spread of the virus.

Due to the continuous fears of infection, Mona was forced into having a c-section during the pandemic, thus staying under treatment for a whole month after delivery.

“During my pregnancy, I did not know if hospitals would admit me or not,” says Mona “I kept asking my doctor to come to the hospital to follow-up my pregnancy, but she refused to come unless there was an emergency delivery.”

When Mona felt the time for delivery approaching, it was 4:00 AM in the morning, she tried to postpone going to the hospital, fearing infection by the virus, which led to her being forced to have a c-section. Her doctor told her that natural delivery would harm the baby.

A week after giving birth, Mona was not feeling well. The surgery’s pain and postnatal problems continued. She called her doctor, but her number was out of coverage and her clinic was naturally closed because of the curfew. When Mona’s condition got worse, she was transferred to Faraman hospital in Qameshli town in Hasaka governorate.

In the hospital, the doctor carried out an examination that revealed her need for a womb cleaning, as her wound was infected. She got several medicines, but after three days she did not get better. She called her doctor again, asking her to come back to the hospital regardless the fears of the virus infection. It turned out that the wound infections are getting worse, and Mona is still under treatment after 16 days of delivery.

Mona explains that if not for the lockdown, she would have been able to have her pregnancy followed-up properly avoiding all these problems.

Pregnant women malnutrition

Last delivery for Wi’am (pseudo name), who lives in Ras Al’ain, was ten years ago. She has three children, who were all born through c-sections, but she did not know that when she got pregnant once again, she will go through all these hardships.

During her pregnancy, Wi’am had to move to Ras Al’ain town. Her husband lost his job as a cap driver on the beginning of the Coronavirus crisis, in parallel with a devaluation of Syrian lira, and rising prices of all commodities and goods in Syria, which deprived her of the most basic food needs, leading eventually to her newborn suffering lack of oxygen.

“I was scared in the hospital,” Wi’am says, “I could not touch anything. Nobody came to visit me because of the lockdown measures and the fear of the virus.”

She adds that after giving birth, she had to drink large quantities of tea, with bread, though her body needed better food, because the shops were closed.

With her delivery approaching, Narmeen (false name) also worries about the after giving birth expenses, because her husband lost his job.

“I think of babies’ milk, and diapers whose prices are becoming extremely high,” Narmeen says, “I will need babies’ milk because I have anemia which makes me unable to breast feed my baby.”

She adds: “My husband lost his job, which affected my condition as a pregnant woman. I did not have fruit for a long time, and I do not get the healthcare essential for pregnant women because of their high high price.”

In her last visit to her doctor, before lockdown was imposed, Narmeen was told she has anemia, and her baby suffered from malnutrition. He prescribed some medicines for her, but she could not afford to buy them.

Doctor Manal Mohamed, the co-director of health authority in Syrian Jazeera, points out that “the virus cannot penetrate the placenta; thus, it cannot affect the baby in mother’s womb.”

He explains that in the hospitals of “self-administration” territories, some operation rooms were set aside for natural delivery and c-sections during the time of the Coronavirus pandemic. But this is not true for all areas. Some villages have no medical centers specialized in delivery and pregnancy follow-up.

On her side, Marwa Abbas, an Obstetrician and Gynecologist, reveals that the clinics are closed throughout the curfew time. She follows-up pregnancies on phone and through internet social media applications, which deprives the pregnant woman of being monitored using the echo device.

She explains that the baby gets its nourishment from its mother’s body once it is attached to the womb, so the mother needs focus and organization of feeding, which most of the pregnant women were denied during to Coronavirus time, along with access to hospitals.

She adds that the virus is more dangerous for pregnant women compared to others as pregnancy jeopardizes their immunity, which shows in fatigue and nausea suffered by pregnant women because of low immunity.

This report was prepared under supervision of the "Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism" (SIRAJ).

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Join the Conversation

جيسيكا ملو فالنتاين -

10 hours agoجميل جدا أن تقدر كل المشاعر لأنها جميعا مهمة. شكرا على هذا المقال المشبع بالعواطف. احببت جدا خط...

Tayma Shrit -

2 days agoمدينتي التي فارقتها منذ أكثر من 10 سنين، مختلفة وغريبة جداً عمّا كانت سابقاً، للأسف.

Anonymous user -

2 days agoفوزي رياض الشاذلي: هل هناك موقع إلكتروني أو صحيفة أو مجلة في الدول العربية لا تتطرق فيها يوميا...

Anonymous user -

2 days agoاهم نتيجة للرد الايراني الذي أعلنه قبل ساعات قبل حدوثه ، والذي كان لاينوي فيه احداث أضرار...

Samah Al Jundi-Pfaff -

3 days agoأرسل لك بعضا من الألفة من مدينة ألمانية صغيرة... تابعي الكتابة ونشر الألفة

Samah Al Jundi-Pfaff -

3 days agoاللاذقية وأسرارها وقصصها .... هل من مزيد؟ بالانتظار