Under the alias of Haj Yunis (Jonah) al-Masri, Italian explorer Ludovico di Varthema presented himself to the people of Hijaz (western modern-day Saudi Arabia and home to Mecca and Medina), which he reached via a pilgrims caravan from Damascus. He had as a Mamluk guard after bribing the organisers..

Varthema’s journey (1503-1509) was one of many undertaken by European orientalist to the holy Islamic lands for intelligence gathering purposes, returning home after gathering information on the social, political and economic dimensions.

Varthema: a Journey Funded by the King of Portugal

Varthema’s journey was undertaken in line with Portuguese efforts to discover routes to the riches of the East, as well as to besiege and encircle the Islamic world - part of what they had named the Reconquista, which stretched from the year 718 to 1492, witnessing the fall of the Islamic Kingdom of Granada on the Iberian peninsula as noted by Abd al-Rahman Abdullah al-Sheikh in the introduction to his translation of the English version of the book “The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema”, originally published in New York in 1863 by John Winter Jones.

This journey was funded by the Portuguese King Manuel I, and took place almost simultaneously to the expeditions of Vasco Da Gama - the first of which arrived in India’s Calcutta after circumnavigating the African continent in 1498, to be followed by his second trip in 1502.

Indeed, while Varthema sailed from Venice - with his destinations including Egypt, the Levant, the Hijaz, Yemen and the Persian Gulf - Portugal’s fleets were themselves establishing commercial ports on the Indian coasts and bombarding its cities.

Nonetheless, al-Sheikh points out: “If Da Gama’s mission had ended with the discovery of the naval route to India, Varthema’s mission was more complicated: he was tasked with describing the customs and habits of the peoples of the territories he passed on his way to India, as well as in India itself (Varthema had arrived in India in his travels and wrote of it). He was also tasked to report on their armies especially as it related to cannons [artillery], their agricultural and manufacturing products - especially those with value in world trade; in short, his task was to comprehensively gather intelligence on all of the peoples and groups that he encountered, especially the Islamic ones.”

Varthema arrived in Mecca in May 1503, proceeding to describe and report on its buildings, environment and Muslim rituals. He would compare the Grand Mosque at Mecca to Rome’s ancient coliseums, and also mentioned the water of the Zamzam well, reporting that Muslims use it to absolve themselves of their sins.

Leblich: Napoleon’s Agent

Along the same route, Spanish traveler Domingo Badia y Leblich undertook his journey to the East and the Hijaz amidst an increase in French ambitions and interests in the East in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In his book, “The Ink Caravan: the Western Travelers to the Arabian Peninsula and Gulf (1762-1950)”, Samir Atallah describes how Leblich served as a secret agent sent by Napoleon Bonaparte in a long and complicated mission that began in 1803 in Tangier where he arrived pretending that he was the Amir (prince) “Ali Bey al-Abbassi”, on his way to Alexandria and then Mecca.

Accordingly, “Ali Bey” travelled to Morocco, where he presented a display of affluence and standing, staying there for two years before departing in a grand pilgrimage convoy.

In Cairo, Leblich met Egypt’s governor Muhammad Ali Pasha, who seems to have known that Leblich had no relation whatsoever to the Abbasids he claimed to be a descendent of; nonetheless, the Pasha (governor) allowed him to continue on his way, as he believed that Leblich could play a role in exacerbating the competition and rivalry between the major powers at the time - which Ali Pasha believed would come in the favor of his goals of building a modern state in Egypt, as Atallah narrates.

Under the alias Hajj Yunis al-Masri, Ludovico di Varthema went to #Hajj and gathered intelligence on the social, political and economic dimensions of the Islamic lands for the King of Portugal who was paving his route to India.

Orientalist Leon Roches worked with the Emir Abdelkader for years, faked Islam, then went to #Hajj, seeking a Fatwa endorsing the French occupation of Algeria

Working for Napoleon and disguised as Aly Bey al-Abbassi, Spanish traveler Domingo Badia y Leblich went to Hijaz amidst an increase in French ambitions and interests in the East in the late eighteenth.

Thus on the 15th of December 1806, “al-Abbassi” departed to Mecca; however, before his arrival there Muhammad Ali Pasha had dispatched a messenger to alert the Sharif (traditional steward of the Holy Cities) of Mecca, Yahya ibn Surur, of the arrival of this mysterious man. The Sharif would subsequently summon Leblich on his arrival, asking where he had come from, and receiving the response that he had arrived from Aleppo. The Sharif proceeded to question Leblich of the wars in Europe taking place at the time and France’s intentions in the Arabian Peninsula, before finally praising his Arabic and deciding to designate a personal escort to accompany him.

Four days later, “Ali Bey” departed to Jeddah and then Yanbu, where he was discovered and subsequently expelled by the local officials - leaving Leblich to return to Cairo, and subsequently Europe, where he remained in Napoleon’s service until his death.

Leblich would nonetheless attempt to return once again in 1818 - but would only reach an area a short distance past the gates of Damascus before dying of dysentery (according to British sources) or by poison (according to the French) - with his mysterious death serving as the last puzzle in the life of a highly ambiguous man, according to Atallah.

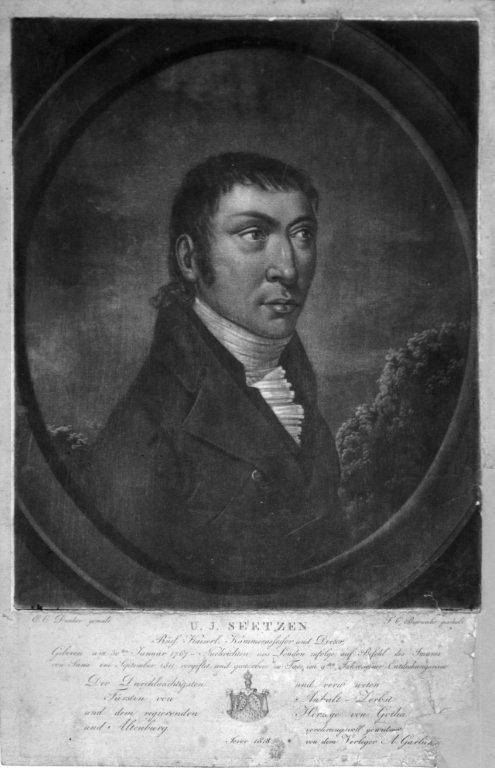

Seetzen: Espionage for Russia’s Tsar

At the time “Aly Bey al-Abbassi” was departing from Cairo to the Hijaz in December 1806, an agent of another state was attempting to launch an expedition from the Egyptian capital to the Hijaz for a similar goal - this time however, for the benefit of the Russians, though he is a German.

The man in question was Ulrich Jasper Seetzen: a 39-year old who had studied medicine, botany and mining engineering, as well as the Arabic language.

In Atallah’s words, “Seetzen had given himself the title of Orientalist, but his real mission was to send reports to the Tsar Alexander I about the military situation in Asia Minor [modern-day Turkey], which had stood as a bulwark against Russian expansionism towards India.”

In order to afford his journey with the necessary degree of credibility, Seetzen would travel to Mecca to carry out the Hajj pilgrimage, before returning to Cairo via Damascus and Aleppo disguised as a beggar - indeed, dissolving amongst the people as a real beggar for three years, before returning under the moniker of “Moses” the doctor.

From Cairo, Seetzen travelled in a caravan to Suez, from which he took a ship to Yanbu on the Hijazi coast. However, he was prevented from entering the city, and thus proceeded to sail to Jeddah, from which he was able to infiltrate into Mecca followed by Medina in 1809. Seetzen was however arrested in Medina and brought before the city’s officials; he claimed to have adopted Islam recently, but was nonetheless expelled - subsequently returning to Mecca where he drew maps of its roads and collected information on the major currents of thought amongst the Islamic groupings, Atallah relates.

Seetzen would depart to Yemen in March 1810, where he stayed until his death in September 1811. His body was found near the city of Ta’iz, possibly having been poisoned after his real identity was discovered, according to Atallah.

Burckhardt: Discovering Areas Unknown by the English

Also during this period, the Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt embarked on a journey on behalf of the African Association (founded in London in 1788), with the task of discovering remote and unknown territories which could be earmarked for British colonial domination.

In his book “Exploring the Golan 1880-1885: Adventurers, Spies and Priests”, Taysir Khalaf relates that the plan was built on Burckhardt first travelling to Syria to study Arabic, before heading to the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt, finally ending in Timbaktu, Mali, which he did not set eyes on having died before reaching it.

The Swiss traveler would be well-prepared for the journey: learning Arabic in Cambridge and then undergoing an intensive course in which he learned the fundamentals of the study of minerals, chemistry, astronomy, medicine and surgery. Furthermore, Burckhardt would also be trained to withstand the likely hardships that he would encounter in his journey.

In May 1809, Burckardt would depart England to the island of Malta, where he spent approximately seven weeks to learn what he further could of Arabic - as well as to develop his disguise as a Muslim Indian trader who wanted to visit Syria.

According to Khalaf, “Burckhardt arrived in Aleppo where he adopted the name of Sheikh Ibrahim ibn Abdullah - a Muslim trader and Indian traveler who carried a recommendation letter from the East India Company to deliver to the British consul in Aleppo. Burckhardt would embark upon an intensive study of Arabic until he became proficient in it, and also studied the Qur’an to the extent that he would come to explain some of the holy verses that were difficult for some to understand.”

In June 1812, Burckhardt finally headed to Egypt, arriving in September. He requested from the governor Muhammad Ali Pasha to allow him to undertake the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Pasha knew however of Burckhardt’s real name and his relationship with the English, and thus summoned two scholars to test him; these however would ultimately verify his claim of conversion to Islam.

Thus Burckhardt would finally travel to Mecca on the 18th of September 1814, remaining there until January 1815 - after having undertaken the Hajj like any other Muslim pilgrim. Burckhardt would then head to Medina, where he would record 350 pages of observations which he sent back to the African Association; these were published in his books “Travels in Arabia” and “Notes on the Bedouins and Wahhabis.”

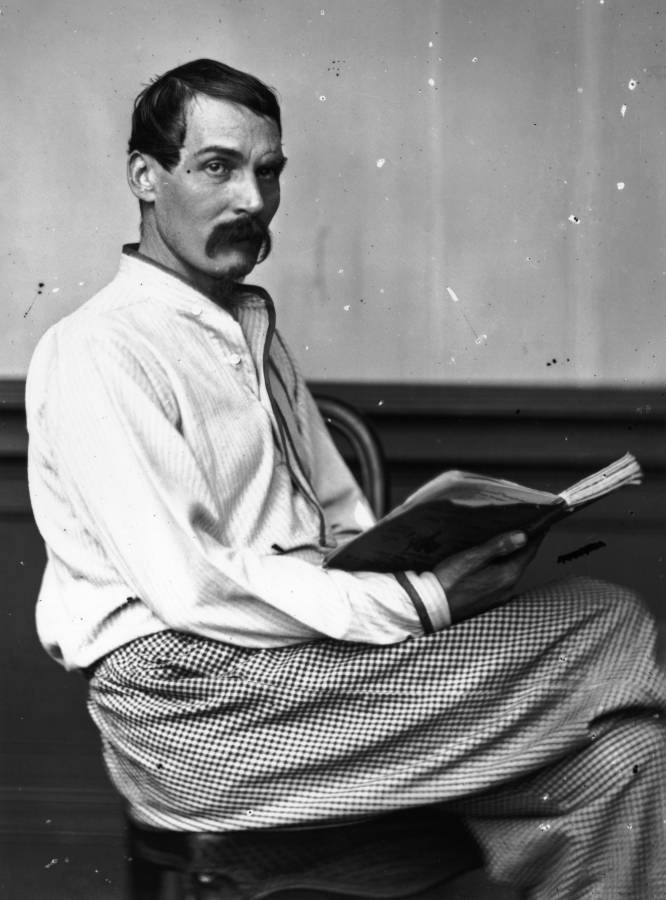

Burton: Exploring Remote Areas

Also for espionage purposes, the British explorer Richard Francis Burton visited the Hijaz and undertook the Hajj pilgrimage. Atallah notes that Burton was an officer with the rank of Second Lieutenant in the British East India Company, which allowed him to reside in Mumbai for an extensive period of time, where he displayed an exceptional ability to learn languages and regional dialects.

In 1852, Burton offered his services to the British Royal Geographical Society to explore the largely-unknown regions of the eastern and central Arabian peninsula; the mission was also important for his attempts to find a solution to the age-old deficiency of the British Army in India: namely, attempting to procure more Arabian camels.

Dressed as a Persian noble, Burton departed the English port of Southampton in April 1853, deciding to comprehensively adopt the persona of a Muslim man in all of its minute details, and training to that end during his journey.

When Burton arrived in Cairo, he enrolled in the renowned Al-Azhar University to learn more about Islam and its religious obligations, before departing to Medina, where he arrived in July 1853. There, he would spend more than a month compiling more than an entire volume of observations, before travelling to Mecca and carrying out the Hajj pilgrimage.

Burton would take two years before finishing his book, “Pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina”; the book would not only encompass mere descriptions of the cities, but would comprise a comprehensive and detailed study of the lives of the Bedouin who fascinated Burton, Atallah notes.

In the meantime, Burton did not forget his dream of extending British rule over the Arabian Peninsula, offering many proposals in his book titled “Winning over the Bedouin”: entailing conscripting the Bedouin in service of the Empire, arguing that they would form an “excellent infantry battalion.”

Léon Roches: Seeking a Religious Fatwa

Meanwhile, the Frenchman Léon Roches also disguised himself during his trip to the holy sites - albeit for considerably different reasons: his task was not intelligence-gathering, but the execution of a specific mission rooted in a “religious Fatwa (ruling).”

In the introduction to his translation of the book “Thirty-two years in the fold of Islam: the memoirs of Léon Roches on his trip to the Hijaz”, the writer Mohammed Khair bin Mahmoud al-Biqa’i notes that Roches’s father had participated in the French military campaign in Algeria in 1830, where he settled and invited his son to join him; the latter eventually did so in June 1932, where he learned Arabic and intermingled with the Algerian population in coffee-houses and Sharia (Islamic Law) Court sittings, before taking on the role of translator for the French administration in Algeria.

During the truce between the Algerian rebel Emir Abdelkader and the French Administration, as per the 1837 Treaty of Tafna, Roches joined the service of the Emir and accompanied him during his internal battles, travels and meetings - eventually rising to become one of his personal writers. Roches would also declare his conversion to Islam, and was subsequently sent by the Emir to his own teacher who had taught him the faith; he would also take a Muslim wife.

However, relations would deteriorate between the Emir and France once again in 1839, prompting Roches to escape and return to his own people after having learnt the Emir’s secrets; he further declared that he was not a Muslim, and was spying on the Emir and the Muslim community.

When Marshal Thomas Bugeaud became the Governor-General of Algeria in 1841, the French authorities found common ground with some Sufi leaders to formulate a religious ruling (Fatwa) which would permit Algeria’s Muslims to live under French rule, while calling upon them to abandon the Jihad (holy war) against them; this was justified as failing to do so would constitute “placing oneself in certain annihilation”, al-Biqa’i relates.

In order for the Fatwa to have the desired effect with the Algerians however, its formulators considered it necessary to obtain the approval of the influential religious centres whose Fatwas were followed by Algerian Muslims, such as those in Kairouan (modern-day Tunisia), Al-Azhar (Cairo) and the two Holy Sites (Mecca and Medina). Roches was nominated for the task, and was joined by some Sufis who were appointed to provide him with the necessary cover; meanwhile, a deposit of golden coins was placed at his command to distribute whenever needed, while instructions were delivered to the French consuls in Cairo and Jeddah to facilitate his mission.

According to al-Biqa’i, the mission entrusted to Roches - who would take on the name “Omar ibn Abdullah” - was filled with danger and risks, not least in Mecca where he performed the pilgrimage. Indeed, here he would be discovered by Algerian pilgrims who outwardly declared the truth of his identity, leading to his arrest. Roches was subsequently muzzled and placed on the back of a camel, Roches believed that he was on the verge of a certain death.

The truth is, the Grand Sharif of Mecca, Muhammed Bin Awn, knew of Roches’ visit and had ordered him closely monitored - albeit without his knowledge - in order to protect him from any harm.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Join the Conversation

Anonymous user -

1 day agoUn message privé pour l'écrivain svp débloquer moi sur Facebook

Anonymous user -

2 days agoالبرتغال تغلق باب الهجرة قريبا جدااا

Jong Lona -

2 days agoأغلبهم ياخذون سوريا لان العراقيات عندهم عشيرة حتى لو ضربها أو عنقها تقدر تروح على أهلها واهلها...

ghdr brhm -

2 days ago❤️❤️

جيسيكا ملو فالنتاين -

5 days agoجميل جدا أن تقدر كل المشاعر لأنها جميعا مهمة. شكرا على هذا المقال المشبع بالعواطف. احببت جدا خط...

Tayma Shrit -

6 days agoمدينتي التي فارقتها منذ أكثر من 10 سنين، مختلفة وغريبة جداً عمّا كانت سابقاً، للأسف.