I always remind myself that my issue with Israel is a personal one. That it is necessary to transform everything that the Zionist movement did to us into personal details.

I always remind myself that my issue with Israel is a personal one. That it is necessary to transform everything that the Zionist movement did to us into personal details.

There is the story of the Palestinian people, which is vast and tragic and continuous, but within that the personal stories and details got lost. Stories of love, the conversations of neighbors, wedding seasons, sexual affairs, and the story of how my great grandmother Lutfia decided to name her daughter Salma in 1936.

I am writing this today not just to tell my friends about it or use it in interviews to talk about being a Palestinian. I am writing as I mourn the death of my maternal grandmother, Salma Jeries Jad’oun Haddad on the morning of March 13, 2019.

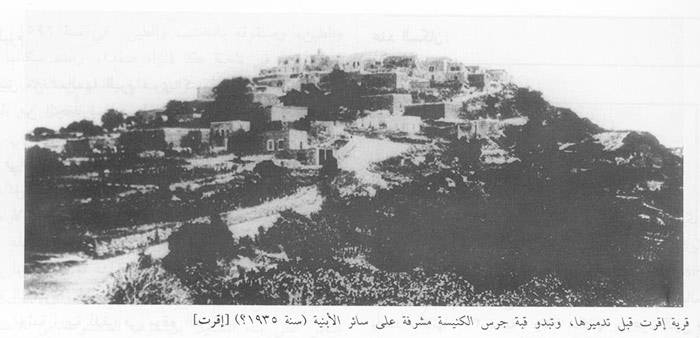

She was born in the village of Iqrith in 1936, and she and her family were expelled to the village of Rama, where she met my grandfather Youssef Tamer Haddad, who became her sweetheart, then her husband when they married in 1955 and the father of her daughters and son.

My grandmother, like my grandfather, was buried after her funeral on Thursday, March 14, 2019, in Haifa, the city where my grandfather moved to in the beginning of the 1980s after leaving Rama. She was buried in the village where she was born and was expelled from when she was 12 years old.

The people of the village of Iqrath, like the people of its sister village of Kafar Birem return to their land only when they are dead, in coffins that are buried in the dirt.

The Right of Return for the dead

Since my grandmother can only return to her land in a coffin, my issue with Israel can only be personal. Although it is important to bury bodies in the place where they were born, this symbolism has an additional dimension since Israel sees that "the only good Arab is the dead Arab" (the racist expression that is often used by right-wing Israelis).

Since my grandmother can only return to her land in a coffin, my issue with Israel can only be personal.

How, then, can Israel's decision to allow the people of Iqrith and Kafar Birem to bury their dead in their land be interpreted, given that there is a ruling by the Supreme Court of Justice that allows the return of the people of the two villages to them?

The villages of Iqrith and Kafar Birem are like any village in Palestine occupied by the Zionist movement in 1948. However, what is special about the story of these two villages is that the Israeli army had requested at the end of 1948 that the residents of Iqrith and Kafar Birem leave the villages for two weeks while the army secured the border with Lebanon.

On Christmas Eve, 1951, Israel demolished all the houses of the village, which had a population of 490 in 1945. Some of the villagers fled to Lebanon and the others to neighboring Palestinian villages. In 1954, the Supreme Court of Justice in Israel approved the return of the people of Iqrith and Kafar Birem. However, this decision prove to be futile, and pressure to apply it continues to this day.

In 1972, Israel agreed to open and renovate the village cemeteries and bury the dead there.

Sense of guilt and daily loss

I left Acre and Haifa to Berlin about two years ago. One of the reasons that led me to this important step in my life was my need, as a Palestinian born in Acre and carrying an Israeli passport, to be in an environment that allows me to communicate and meet physically with friends and family from my natural Arab millieu. The possibility that a friend from Damascus could come visit me in Haifa to sample my grandmother's bread, or to fall in love with a young Tunisian who lives on my street, are things rendered impossible by the Zionist colonization of Palestine.

Berlin granted me a parallel world I wanted to live in, even though the reasons that brought many to it involved political, social and personal crises. Although Berlin has neither sea nor sun, the dialects of the people of Daraa, Algiers, Alexandria and Sanaa warm my heart.

However, since the moment I decided to leave Palestine, I was constantly assailed by guilt, because I had forsaken my responsibility for my country and its people. This feeling is legitimate and familiar, and I learned to adapt to it. It was the price I had to pay, and I still do, but it was the price of creating alternative forms of communication that did not distance me from my native land, even though I was far from it geographically.

"Death does not hurt the dead, death hurts the living."

But what I cannot adapt to, and I think I never will, is the sense of loss that involves missing the daily details of the place and those I love. I l miss my brothers worrying about me, the jokes that my mother laughs at, and I lost the chance see my grandmother fighting against the death that she feared.

She always used to say, quoting Mahmoud Darwish: "Death does not hurt the dead, death hurts the living."

The daily fear of loss

I last saw her few months ago, on Christmas and the New Year. She scolded me as usual for being far away. She asked me her constant question about when I would return to Palestine. And I joked as usual, "Teta, I am happy. Why would I come back?”

She said to me, as always: "I am happiest when you are beside your mother."

I understood my grandmother and her anxiety, and I understood her fear of sudden loss, this woman for whom the only safe place is family. She was expelled from her home and her brother died when he was 18 years old, of cancer.

A woman constantly assailed by grief, who spent every day fearing a new loss. She stopped singing and dancing at weddings. All expressions of joy stopped. She sang songs of lament for the dead at the moment of their departure, as though, ever since she had known life, she had known its sad truth, which was affirmed throughout her own time.

The death of my grandmother is not just a personal issue

I was supposed to go to Haifa for a two-week visit on Friday, March 15. At the beginning of the week, my mother told me that my grandmother had returned to the hospital. Her condition had been stable over the past few days but she still required medical observation. I was glad that I planned to visit without knowing how necessary it would be, as it was partly to attend the Haifa independent Film Festival, which was being held for its fourth year.

I had pulled out the tape recorder in my room in Berlin so I would not forget it, because this time I wanted to record the stories my grandmother would keep telling, with new details being added every time. But Salma did not wait for me.

My grandmother left. Although the pain of the family is primarily personal, my grandmother's death is not only a personal issue.

My grandmother left. Although the pain of the family is primarily personal, my grandmother's death is not only a personal issue. On the threshold of the 71st anniversary of the Nakba of Palestine and its people, it seems that we realized too late that we need to gather the personal stories of those who saw it with their eyes, lived it with their bodies and had the memories accompany them for life.

Today I will try to write down what my grandmother, who never told stories directly about 1948 (as if covering over the pain with personal stories), told us about her grandmother who had snuck into Lebanon in search of her daughter, of burning her legs with oil while frying fish days before her wedding. Her stories, like all our continuing stories, are personal stories about the Nakba.

On my last visit to Palestine, I said that I needed to keep visiting my country, even for some days, just to remember who I am. With the latest news, I visited Palestine for the first time without my grandmother receiving me, or asking me, "When will you return to Acre?"

I arrived too late, but I know that all my travels will not teach me my grandmother's most important lesson: how a heart that endured oppression can remain good and tender.

Through the kindness of my grandmother’s heart, that very personal space, I will cling to a hope that surpasses me and my person. I pray I will not be disappointed.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Join the Conversation

Tester WhiteBeard -

2 hours agoEgypt

Tester WhiteBeard -

2 hours agoGreat

Ayar Abdelkreem -

19 hours agoكانت مكتوبة مقال رأي وتم رفضه من رئيسة التحرير،

Ayar Abdelkreem -

19 hours agoكانت فكرتي

Samah Al Jundi-Pfaff -

1 day agoأرسل لك بعضا من الألفة من مدينة ألمانية صغيرة... تابعي الكتابة ونشر الألفة

Samah Al Jundi-Pfaff -

1 day agoاللاذقية وأسرارها وقصصها .... هل من مزيد؟ بالانتظار